Languages often have multiple words that can mean the same thing. They also have words that can mean many different things depending on the context or situation in which they are used. Saying it is chilly, cool, or brisk this morning basically means the same thing. You might want a jacket. The temperature is low. In cider and wine, there are several words like this, but the use of them defines the context. You may hear some talk about volatile acidity. You may also hear discussion about acetic acid. Sometimes, you might hear the word vinegar. The interesting and sometimes confusing aspect is that from a cider and wine context, these are all referencing the same thing. However, the use of the terms is usually contextual.

In wine and hard cider, volatile acidity is generally referring to acetic acid. Acetic acid is an organic acid and scientifically can also be called ethanoic acid, which relates to how acetic acid is often created through the oxidation of ethanol. Sometimes, acetic acid is called vinegar. This is because the main component of vinegar is acetic acid. Why not just call it all acetic acid instead of volatile acidity or vinegar? The answer is context.

When you make vinegar, the goal is to oxidize all of the ethanol into acetic acid. This requires lots of oxygen and acetic acid bacteria. Yeast or lactic acid bacteria won’t create vinegar. They can create acetic acid, but more on that in a minute. Vinegar only gets created when acetic acid bacteria has access to ethanol and lots of oxygen. Even if cider has high levels of acetic acid bacteria in it, it won’t create acetic acid and ultimately, vinegar unless you give it excessive amounts of oxygen. I used the word excessive on purpose. A bucket with cider sitting in it, even with the lid off, will usually not get enough oxygen to create vinegar. A bucket with a leaking lid, will never create vinegar. To make vinegar, you must aerate the cider. You can pump it in, stir it in, or even rack it in the cider. Just sitting there, won’t provide enough oxygen to create vinegar. Note that I didn’t say acetic acid. I said vinegar.

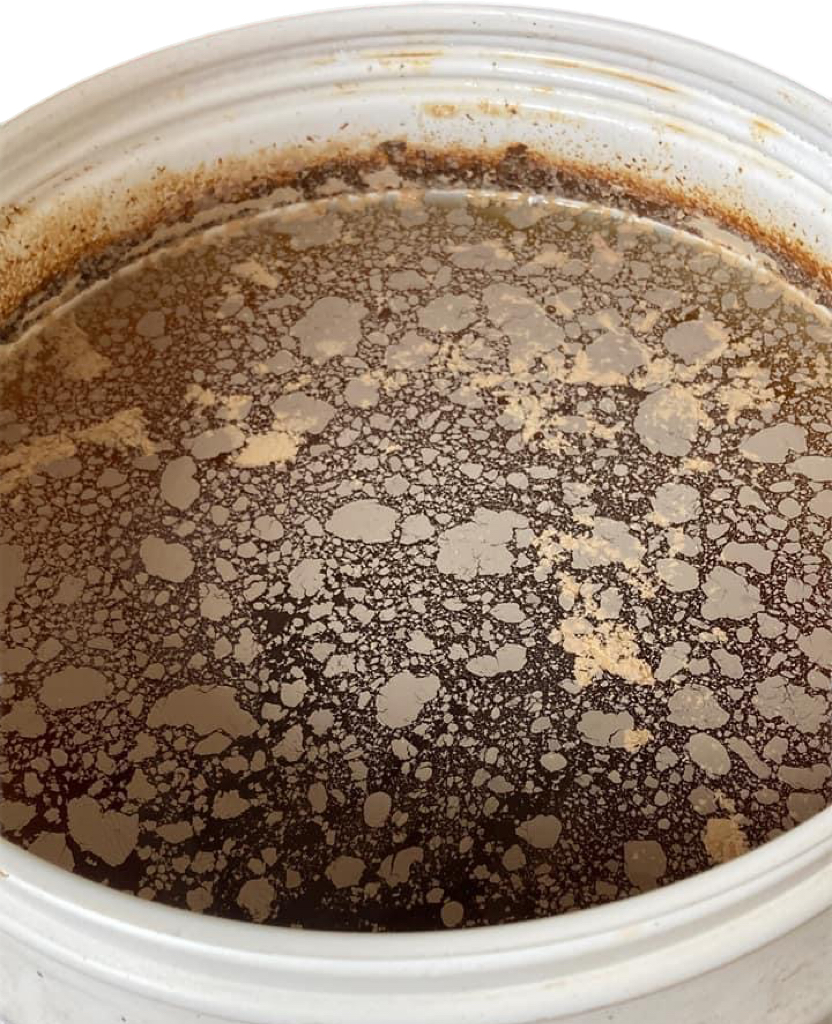

Aging cider in a bucket is a horrible idea, even with a lid that is sealed and leak proof. First, buckets are made of thin plastic, which will allow oxygen to permeate during long-term storage. Second, buckets have a wide headspace area that you can never really fill completely. Have you ever noticed that wood barrels are filled through a bung hole located on the side at the maximum circumference of the barrel. That allows you to fill the barrel 100% full. Buckets don’t allow that. What all this means is that your cider is exposed to oxygen. Not the excessive amounts needed to create vinegar but enough to create volatile acidity. However, you can also experience volatile acidity in an anaerobic environment.

Volatile acidity for cider and wine refers to the perception of acetic acid, which is the most prevalent volatile acid. Malic acid for example, is not a volatile acid. It will create tartness but not the distinct aroma of acetic acid. Volatile acidity means you have enough acetic acid present (~1.5g/l) that it’s noticeable in the aroma and taste, but not enough to be considered vinegar (~30-90g/l). That is because most of the acetic acid present wasn’t created by acetic acidic bacteria but yeast and lactic acid bacteria. Again, this is because vinegar requires excessive amounts of oxygen. Not the levels available when aging, even in a bucket or from racking too frequently or splash racking. Acetic acid is also created in anaerobic environments and yeast and lactic acid bacteria are capable of doing this. Fermentative yeast can enable acetic acid production when it produces glycerol through the glyceropyruvic pathway. Lactic acid bacteria can produce acetic acid during reproduction. What’s interesting is that not all lactic acid bacteria are the same. Some like Oenococcus oeni produce more acetic acid than others. It’s interesting that O. oeni is more of a concern for wine versus cider. This is because Oenococcus oeni is more alcohol tolerant and will survive and thrive in wine but can be suppressed by other lactic acid bacteria at lower alcohol levels(1), like those found in cider.

For cider and wine, volatile acidity and vinegar are both referring to acetic acid. However, the difference between the two is related to how much and how it was created. It also highlights another reason cider and wine are different. Cider’s lower alcohol levels may actually protect against volatile acidity as long as you keep the cider away from oxygen.

(1) P. Ribereau-Gayon and associates, Handbook of Enology Volume 1, The Microbiology of Wine and Vinifications 2nd Edition, Chapter 6-7, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2006 ISBN: 0-470-01034-7

Check out some other interesting articles by Prickly Cider.

Don’t miss any future Mālus Trivium articles. Follow me and you will get a link to my latest article delivered to your inbox. It’s that easy!

Understanding how yeast create great cider will help you make better cider. Knowledge and sharing it is why I wrote my book, launched this website, and provide products and recommendations on The Shop page. It is why I started offering non-Saccharomyces yeast strains in the Cider Yeast section of the shop. If you are interested in supporting PricklyCider.com, check out the shop. As with everything, my goal even with the shop is to help you make better cider.