You must wonder where I find some of my cider words, especially a word like chemoorganotroph. It sounds made up, but I promise that it’s not. I was reading the Handbook of Enology Volume 1 (1), when I came across this gem of a word. The book highlighted how living things are endergonic, meaning they require energy to live and reproduce. Some plants, like apple trees, collect that energy from the sun. These plants are called phototrophs. Some bacteria are chemolithotrophs, which means they obtain energy from the oxidation of materials. This is how bacteria can impact the aging process for cider. However, animals, many bacteria, and fungi (e.g. yeast) are chemoorganotrohs. They obtain energy from the degradation of organic compounds. This energy is usually on the form of adenosine triphosphate or ATP.

For cider, sugars are the most common organic compound used to create ATP. Yeast degrade the sugar into smaller compounds through various pathways. This process is called catabolism. The yeast then join these smaller compounds into larger more complex compounds. This is an anabolic process. Again, different pathways are used to execute these processes. A yeast cells often have multiple pathways that can be used to create needed compounds. The genetic make up (i.e. DNA or genes) of a yeast will define what pathways are available, but it’s not the only factor. The environment in which yeast are living also impacts which pathway can function. Some examples of environmental factors are sugar, oxygen, nutrients, vitamins, ethanol, and even temperature. These all will restrict or enable a pathway.

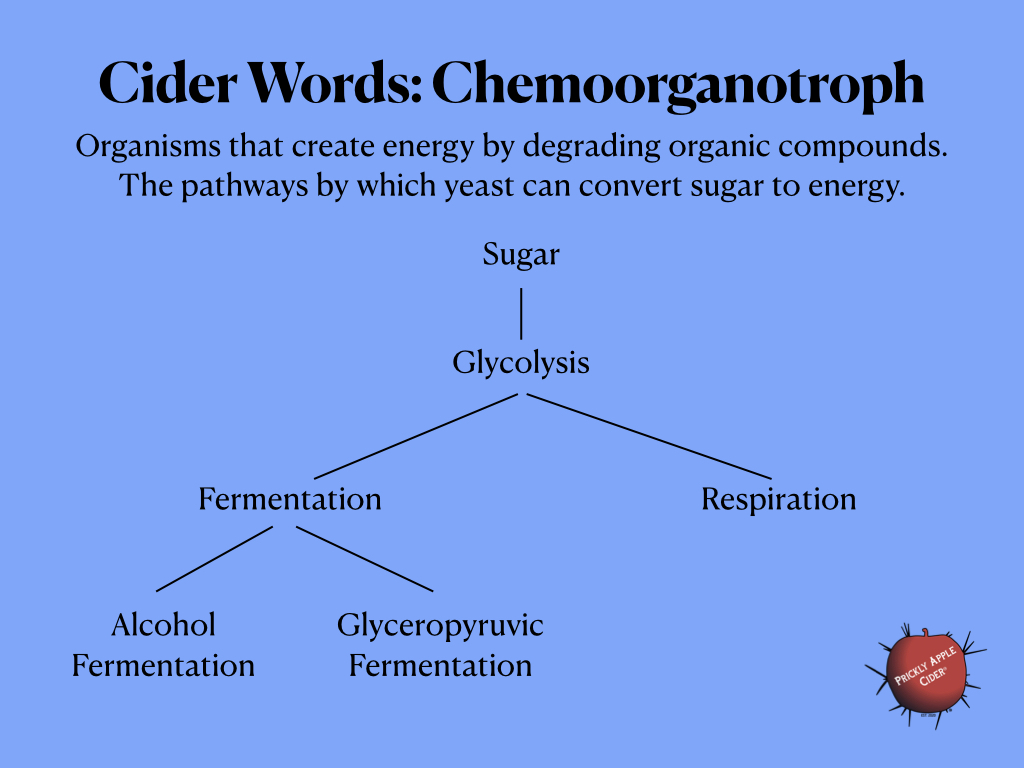

It’s important to remember that yeast want to live and reproduce and they need energy to do this. Since they are chemoorganotrohs, they do this by processing various organic compounds. Fundamentally, this is sugar like glucose, fructose, and sucrose. Generally, there are two main pathways that are available to most yeast, which are fermentation and respiration. Yeast prefer the respiration pathway because it can gain 36 to 38 molecules of ATP per molecule of sugar versus a maximum of two molecules of ATP through the fermentation pathway. However, the sugar concentration in apple juice usually forces yeast to use the fermentation pathway, even when sufficient oxygen is present.

Regardless of the pathway, the first step is the same, which is glycolysis. This is the process where sugar is converted into pyruvate through four stages.

The fermentation pathway actually has main two branches. The most common is the alcohol fermentation branch. This is the pathway branch that converts pyruvate from the glycolysis process into ethanol and carbon dioxide. For Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts, this branch is utilized about 92% of the time(1). This varies by strain. An interesting point is that non-Saccharomyces yeasts tend to have a lower utilization rate. They tend to utilize the second branch, or similar branch, which is the glyceropyruvic pathway, more than the 8% used by Saccharomyces. This pathway turns pyruvate into glycerol, acetaldehyde, and carbon dioxide. One point to note is that glyceropyruvic fermentation doesn’t actually create any ATP. The process creates and uses equal amounts of ATP. What it does do is transfer electronics on the Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NDA) molecule. Yeast use the NDA molecule to support various pathways that unlock nutrients.

So remember, yeast are chemoorganotrophs that are using respiration or fermentation pathways to create the energy they need to survive. Apple juice doesn’t allow much respiration because of its acidity and sugar content so yeast use mostly use alcohol fermentation pathways and to a lessor extent, glyceropyruvic fermentation pathways, to unlock the energy they need from the sugar and nutrients found in the apple juice.

(1) P. Ribereau-Gayon and associates, Handbook of Enology Volume 1, The Microbiology of Wine and Vinifications 2nd Edition, Chapter 2, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2006 ISBN: 0-470-01034-7

Do these words make you want to know more about how to make your own cider? Checkout some of the articles below or search recipes or methods on PricklyCider.com and find even more.

Decoding Yeast Genes: Aroma and Sensory Characteristics

If you took the same juice and fermented it with different yeasts, why would they have different aromas or flavors and even unique mouthfeel and sensory characteristics? Why would one…

Non-Saccharomyces Yeast: Inoculating for Control

This is the third article in my series on non-Saccharomyces yeast. Initially, I reviewed the concept that the yeast commonly used for wine and beer, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is not ideal…

Ehrlich Pathway Explained

Fusel alcohols or what are also called higher alcohol add aromatic complexity to hard cider and other fermented beverages. Yes, too much of them can lead to undesirable or overwhelming…

Respiration versus Fermentation

Have you ever heard that oxygen is bad and to avoid oxygen exposure when fermenting hard cider? It is or at least it can be. Yes, this is another one…

Don’t miss any future Mālus Trivium articles. Follow me and you will get a link to my latest article delivered to your inbox. It’s that easy!